Long Way to cPLA2: How a Nutrition Question Changed Our View of Alzheimer’s

As we enter a new year, I want to wish you a healthy 2026 and share a bit of the story behind our most recent paper (published online today). This work did not begin with a plan to develop a drug. It began with a question that wouldn’t go away.

Around 2015, I was trying to understand why omega-3 fatty acids—especially DHA—were not delivering the benefits we expected in Alzheimer’s disease. The rationale seemed sound. DHA is a major component of the brain, supports synaptic function, and gives rise to lipid mediators that help resolve inflammation. Observational studies consistently linked higher omega-3 levels to lower dementia risk.

Yet clinical trials were largely disappointing.

When we looked more closely, the lack of benefit was not evenly distributed. People who carried the APOE4 gene, the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, appeared to benefit the least. Their blood DHA levels increased with supplementation, but markers of brain delivery rose much less—especially in those with amyloid pathology.

At first, we assumed the explanation would be simple: impaired transport into the brain, or perhaps insufficient dose. But even higher doses failed to normalize the response in APOE4 carriers. That was the first sign that this was not just a nutrition problem.

From levels to dynamics

To move forward, we had to rethink the question. Instead of asking how much DHA was present, we began asking how the brain handles lipids over time.

Imaging and tracer studies suggested something unexpected: cognitively normal APOE4 carriers sometimes showed higher rates of DHA uptake into certain brain regions. Over time, we came to see this not as a sign of sufficiency, but of compensation—the brain pulling in DHA to replace what it was losing or breaking down more rapidly.

This interpretation fit with metabolic studies showing faster DHA turnover in APOE4. It shifted our thinking away from deficiency and toward altered lipid handling inside brain cells.

Why balance mattered more than abundance

As we expanded our analyses, another pattern became hard to ignore. Across blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and eventually brain tissue, APOE4 carriers tended to have lower omega-3–to–omega-6 ratios, particularly DHA relative to arachidonic acid.

That balance matters. Omega-3 and omega-6 fats feed into competing signaling systems. Omega-3–derived mediators generally help resolve inflammation. Arachidonic acid, an omega-6 fat, is the precursor for many inflammatory molecules.

What stood out was that increasing DHA intake did not reliably correct this imbalance in APOE4 carriers. Even when omega-3 levels rose, inflammatory lipid signaling often remained elevated.

This raised a more uncomfortable possibility: APOE4 may actively bias the brain toward inflammation, rather than simply limiting access to protective fats.

Seeing the problem directly in human brains

For years, much of this work relied on indirect measures. A turning point came when we examined human post-mortem brain tissue.

In a study led by Brandon Ebright and colleagues, we analyzed inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators in brains from people with and without Alzheimer’s dementia, stratified by APOE genotype. The findings were sobering.

Alzheimer’s brains showed:

lower omega-3–to–omega-6 ratios

markedly reduced levels of neuroprotectin D1, a DHA-derived molecule linked to neuronal survival

elevated levels of arachidonic-acid–derived inflammatory lipids

What mattered most was how APOE4 modified this picture. In APOE4 carriers with dementia, both inflammatory and pro-resolving mediators were elevated. This pattern is consistent with chronic unresolved inflammation—the system is trying to restore balance, but not succeeding.

Importantly, these lipid signatures correlated with cognitive performance and pathological burden, especially in APOE4 carriers. At that point, lipid dysregulation no longer looked like a bystander. It looked intertwined with the disease process itself.

Why one enzyme kept reappearing

Once we had human brain data, the question narrowed: what controls the release of these lipids?

Again and again, the same enzyme emerged: calcium-dependent phospholipase A2 (cPLA2). When activated, cPLA2 releases arachidonic acid from cell membranes, feeding inflammatory signaling pathways.

Earlier work in our lab, led in large part by Shaowei Wang, showed that APOE4 is associated with persistent activation of cPLA2 in astrocytes, animal models, and human brain tissue. The lipidomics data reinforced this finding.

What became clear was that the problem was not constant triggering, but a failure to turn activation off.

Why this was not an obvious therapeutic path

Even with strong evidence, we were cautious.

cPLA2 is essential for normal brain function. Completely inhibiting it would almost certainly cause harm. And historically, efforts to target cPLA2 failed because available compounds were not selective, did not cross the blood–brain barrier, or worked only in artificial assays.

For a long time, it was not clear that this pathway could be modulated safely in the brain.

The study that tested whether this was even possible

The recent paper grew out of that uncertainty.

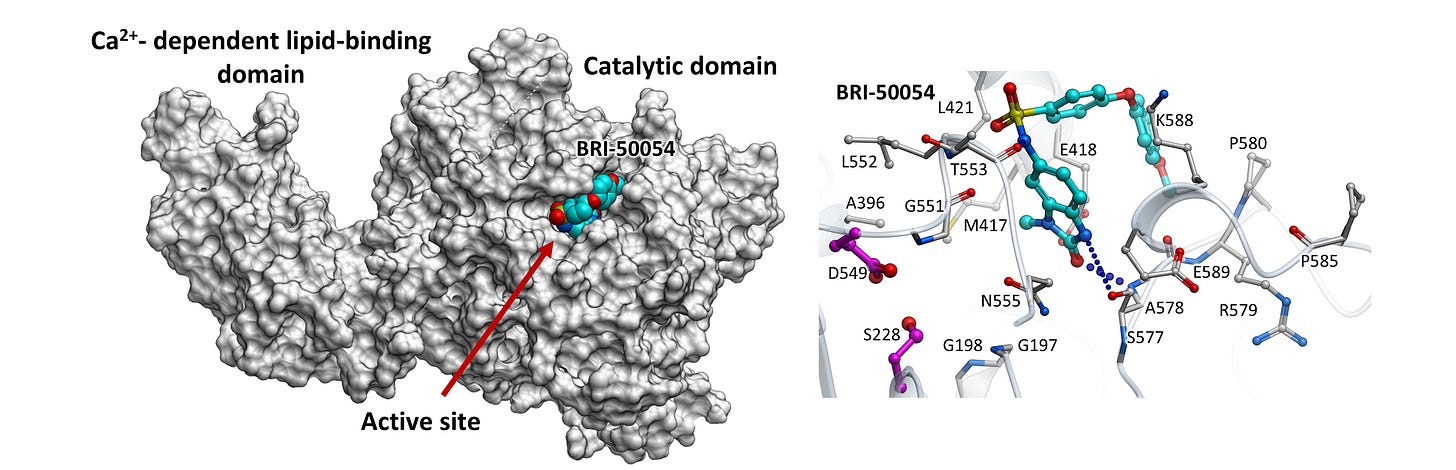

Anastasiia Sadybekov and Marlon Vincent Duro led an effort that began not with existing inhibitors, but with chemical space itself. Using large-scale computational screening, they evaluated billions of potential molecules, prioritizing those predicted to be selective, brain-penetrant, and active under biologically relevant conditions. Anastasiia, under the supervision of Seva Katritch, designed the compounds, and Marlon tested them in the lab. Once we identified the top hits, Stan Louie’s team helped formulate them for administration in animal models.

The figure above shows a first-generation cPLA2 inhibitor that successfully reduced cPLA2 activity in the lab. After multiple rounds of refinement and testing over 3 years, the team identified a compound that reduced pathological cPLA2 activation in brain-relevant cells exposed to Alzheimer’s-related stressors. In mice, the compound reached the brain and shifted lipid signaling away from excessive inflammatory pathways.

These experiments were intentionally narrow. They were designed to answer a single question:

Can pathological cPLA2 activity be modulated in a living brain?

They do not show disease prevention, cognitive benefit, or long-term safety.

What this does—and does not—mean

It would be easy to overinterpret these findings. We try not to.

Alzheimer’s disease is complex. Lipid dysregulation is one part of a much larger system involving protein aggregation, vascular health, metabolism, and aging. Modulating cPLA2 may help in some contexts and not others. Timing, genetics, and duration all matter, and many of those questions remain unanswered.

What this work provides is something more modest, but essential: a way to directly test a mechanism that years of human and experimental data have pointed toward.

Where we go next

Building on nearly a decade of work, our team has now secured NIH support to translate these discoveries into a brain-penetrant, selective inhibitor of cPLA2, with the goal of testing whether targeting inflammation can alter Alzheimer’s risk—particularly in APOE4 carriers. This next phase focuses not on promises, but on carefully determining whether modulating this pathway is safe, feasible, and ultimately meaningful for human disease.

Science moves forward this way more often than not: incrementally, collaboratively, and with humility about what we still don’t know.

For now, that is where we are.

Sadybekov, A.V., Duro, M.V., Wang, S. et al. Development of potent, selective cPLA2 inhibitors for targeting neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. npj Drug Discov. 3, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44386-025-00035-0

Acknowledgment and disclosures: This work is the result of a close collaboration between the Katritch Lab, the Louie Lab, and the Yassine Lab, and was supported by the National Institute on Aging under grant U01AG094622. I am deeply grateful to all of the authors whose tireless work made this research possible: Anastasiia V. Sadybekov, Marlon Vincent Duro, Shaowei Wang, Brandon Ebright, Dante Dikeman, Cristelle Hugo, Bilal Ersen Kerman, Qiu-Lan Ma, Antonina L. Nazarova, Arman A. Sadybekov, and Isaac Asante. I also want to acknowledge PebRx, a company developing cPLA2 inhibitors, which I founded to help translate this research beyond the laboratory.

Thank you for this Dr Yassine for this work. I am glad you have support to follow this and many of us will watch your progress.

A question: Has there been any evidence that recommended inflammation lowering steps (diet, exercise, supplements, medication ) are effective in modulating cPLA2 or is this a process that will run its course and increase inflammation regardless of intervention? Thank you again.

So ideally, we can take LPC-DHA to gain modest entrance to the brain via whatever MFSD2A function we have going for us as APOE4 carriers, and then, when your cPLA2 inhibitor is in market, it can be put to good use, long enough for it to get where it needs to go! This is a really cool time to be alive, for us APOE4 carriers! Best wishes to you and your research teams in 2026!