Why the New Food Pyramid Matters—Especially for the Brain

The new dietary guidelines arrive at a moment when nutrition science is finally catching up with biology.

For decades, Americans were told to focus on nutrients: calories, fat percentages, carbohydrates, cholesterol. Meanwhile, rates of obesity, diabetes, and cognitive decline continued to rise. This wasn’t because people lacked discipline or information—it was because the food environment changed in ways our guidelines failed to confront.

The new food pyramid represents an important course correction. For the first time, food processing—not just nutrients—moves to the center of dietary advice. Whole, minimally processed foods form the foundation. Ultra-processed foods are no longer treated as neutral choices to be “managed,” but as products that should be actively displaced.

That shift matters for weight, for metabolism, and profoundly for the brain.

What Earlier Guidelines Missed

To be clear: earlier dietary guidelines didn’t create ultra-processed foods. Industry did.

Food manufacturers engineered products to be hyper-palatable, easy to overconsume, shelf-stable, and highly profitable—all reinforced by aggressive marketing. They accomplished this through refining, additives, emulsifiers, texture engineering, and flavor manipulation.

What earlier guidelines failed to do was name processing itself as a biological problem.

Ultra-processed foods were treated as ordinary foods that simply required moderation. But these products aren’t neutral. They’re designed to bypass normal appetite regulation.

For years, this was suspected. Then it was tested.

What Happens When You Isolate Processing Itself

In a landmark NIH-led randomized trial led by Kevin Hall, researchers asked a simple question: Does food processing itself cause people to eat more?

Participants lived in a metabolic ward and were fed two diets—one composed largely of ultra-processed foods, one composed of minimally processed whole foods. The diets were matched for calories offered, sugar, fat, fiber, and macronutrient composition. Participants could eat as much or as little as they wanted.

The results were striking.

On the ultra-processed diet, people ate about 500 extra calories per day, ate faster, and gained weight—without feeling satiated or more satisfied. On the whole-food diet, they spontaneously ate less and lost weight.

Nothing about willpower changed. Nothing about nutrients changed. Only processing changed.

This study provided causal evidence that ultra-processed foods promote overeating by disrupting satiety—something older dietary guidelines never adequately addressed.

Why Whole Foods Support Weight Control

Whole foods—whether animal-based or plant-based—retain their natural structure. They require chewing, digestion, and metabolic work. They slow eating, activate fullness hormones, and signal the brain before overeating occurs. This is why diets built around whole foods often lead to weight control without constant restraint.

This matters because midlife obesity, insulin resistance, and hypertension are among the strongest predictors of cognitive decline decades later. Weight regulation isn’t just about appearance or longevity—it’s upstream of brain health.

Red Meat Is Not the Same as Processed Red Meat

Much of the nutrition debate collapses when very different foods are lumped together.

Processed red meat—bacon, sausages, hot dogs, deli meats—is consistently associated with worse health outcomes. These foods are typically ultra-processed, high in sodium, nitrites, and additives, and easy to overconsume.

Whole, unprocessed red meat is a different food entirely. When consumed as part of a balanced, minimally processed diet, whole cuts of meat provide high-quality protein, iron, zinc, B vitamins, and choline—nutrients that support muscle mass, satiety, and metabolic health.

The issue isn’t meat. The issue is processing.

Protein-rich whole foods—animal or plant—help regulate appetite by signaling fullness early and durably.

It Doesn’t Have to Be Meat

None of this means meat is required for health.

Well-designed plant-based diets can be equally supportive—when they’re diverse, protein-adequate, and minimally processed. Traditional plant-forward dietary patterns associated with better metabolic and cognitive outcomes share common features: vegetables and fruits, legumes, nuts and seeds, whole grains, and healthy fats.

What matters is diversity and structure, not dietary identity.

A plant-based diet built on lentils, beans, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and whole grains behaves very differently from one dominated by refined flours, sugary beverages, and packaged substitutes. The brain responds to food quality—not labels.

Why Brain Health Depends on Starting Early

Here’s where the science becomes both clearer and more urgent.

Brain changes associated with dementia begin decades before symptoms appear. Long before memory loss, subtle shifts occur in brain energy metabolism, vascular function, and inflammation. Diet influences all of these systems, but the timing of that influence matters.

Nutrition plays a role at every stage of life. Even in people living with cognitive impairment or dementia, good nutrition supports overall health, reduces frailty, preserves muscle mass, and improves quality of life.

But its preventive power is strongest earlier, when the brain is still metabolically flexible, and damage isn’t yet entrenched. In later stages of disease, nutrition becomes more supportive than transformative. In midlife—or earlier—it may meaningfully shape the trajectory of brain aging.

APOE ε4 and the Case for Personalized Nutrition

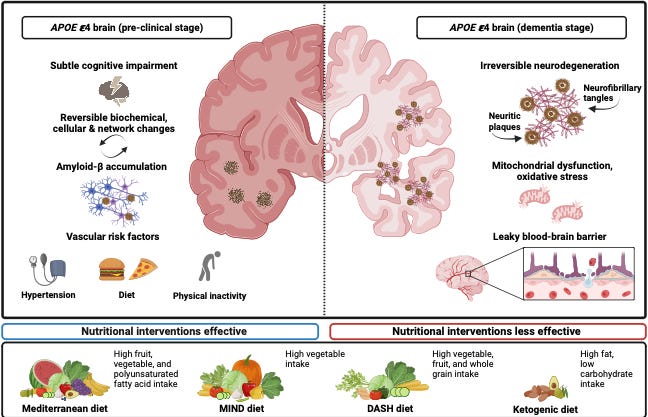

This timing issue is especially important for individuals who carry the APOE ε4 gene copy, the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

APOE ε4 affects the brain in ways that make it more vulnerable to metabolic stress: less efficient lipid transport and repair, greater susceptibility to insulin resistance, increased inflammation, and earlier disruption of the blood–brain barrier. These changes develop gradually, often beginning in midlife—long before any symptoms appear.

For APOE ε4 carriers, this has two important implications.

First, diet quality may matter more, earlier. Diets dominated by ultra-processed foods, refined carbohydrates, and excess energy appear especially mismatched to the biology of the APOE ε4 brain.

Second, by the time cognitive symptoms emerge, the brain’s ability to respond to nutritional interventions may already be constrained. Changes in nutrient transport, mitochondrial efficiency, and vascular integrity limit how much benefit late interventions can provide. The figure below illustrates why interventions during the cognitively unimpaired stage are likely to be more effective than when dementia is diagnosed.

This helps explain why nutrition trials often show limited effects in older APOE ε4 carriers—and why this shouldn’t be interpreted as evidence that nutrition doesn’t matter for them. Rather, it underscores the importance of starting earlier.

Where Supplements and Personalization Fit

This perspective also clarifies the role of supplements.

Supplements aren’t a substitute for food quality. When used broadly, without regard to diet or individual biology, they rarely prevent cognitive decline.

At the same time, supplements aren’t irrelevant. There are situations where targeted supplementation may be appropriate—such as in individuals with documented deficiencies, restricted diets, impaired absorption, or age-related metabolic changes. In these contexts, supplements can help fill gaps, particularly when layered on top of a high-quality dietary pattern.

This is where personalized nutrition becomes important.

Personalized medicine doesn’t mean chasing pills or extreme diets. It means recognizing that risk isn’t evenly distributed, and that some individuals—such as APOE ε4 carriers—may benefit from earlier, more intentional attention to metabolic and dietary health.

Food quality does the heavy lifting. Personalization helps fine-tune the approach.

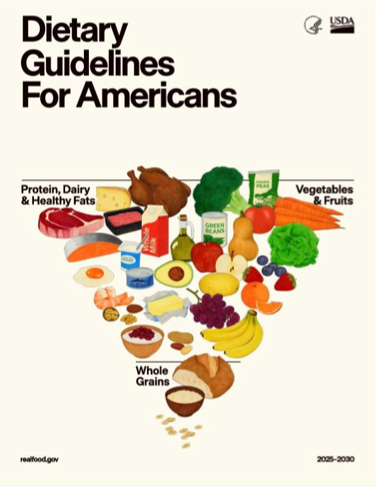

Why the New Food Pyramid Is a Step Forward

The new food pyramid reflects these biological realities.

It doesn’t prescribe a single ideology. It allows for animal-based diets, plant-based diets, and everything in between. What matters is food quality.

By prioritizing whole, minimally processed foods, the pyramid aligns guidelines with how appetite, metabolism, and brain health actually work over time. Weight regulation becomes a byproduct of satiety. Brain protection becomes a downstream effect of metabolic health.

The pyramid isn’t a solution by itself. But it finally names the central problem: a food environment dominated by ultra-processed products is incompatible with long-term metabolic and brain health.

The Takeaway

Brain health is built slowly, quietly, and early.

It’s shaped not by a single superfood, supplement, or diet trend, but by daily patterns repeated over years. Diets dominated by ultra-processed foods make it harder for the body to regulate appetite, harder to maintain metabolic health, and harder for the brain to meet its energy demands with age.

The solution doesn’t require perfection or ideology.

For most people, there is no need to eliminate entire food groups. No need for supplements to compensate for a broken food environment.

You need food that still looks like food—and you need to start early.

Whether your diet includes animal foods, is mostly plant-based, or falls somewhere in between, the principle is the same: prioritize whole, minimally processed foods chosen for diversity, nourishment, and satiety. Over time, the body regulates itself more easily, and the brain is better protected. And for APOE ε4 carriers, this is more urgent and personalized. Nutrition trials are evolving, and we are on the right track.

This is an excellent (and overdue) course correction: moving food processing to the center of dietary guidance aligns far better with human physiology than the old “macro math” framing. Your use of the Kevin Hall NIH metabolic-ward trial is especially powerful because it isolates processing itself, when the diets were matched for offered calories/macros/sugar/fiber, participants still ate ~500 kcal/day more and gained weight on the ultra-processed diet, largely via faster eating and weaker satiety signaling. That’s causal evidence, not moralizing.

I also really appreciated the brain-health lens and the timing argument: midlife metabolic dysfunction (insulin resistance, hypertension, visceral adiposity) is upstream of later cognitive decline, and dietary patterns that displace ultra-processed foods are a practical way to reduce that risk years before symptoms ever appear.

Your nuance on “meat vs processed meat” is another important public-service point; people get stuck in ideology when the biology often comes down to structure, additives, sodium/nitrites, and hyper-palatability. And the APOE ε4 discussion is clinically helpful: it makes it easier to understand why late-stage nutrition trials can disappoint without implying diet is irrelevant; risk biology and therapeutic windows matter.

Thanks Dr. Yassine for this interesting article. Glad I've just discovered your Substack. I miss seeing your posts since leaving the Facebook 4/4 group.