The Bend in the Curve: APOE ε4, Cognition, and Prevention

Merry Christmas, everyone. 🎄

I start this post with a well-characterized study population, because it provides informative data on how APOE ε4 affects cognitive functions.

The Religious Orders Study (ROS) is a long-running collaboration between Rush University and partner U.S. medical centers, under the leadership of David Bennet. It follows older religious clergy—nuns, priests, and brothers—who agree to two things that rarely come together at scale: annual medical and cognitive evaluations during life, and brain donation after death. That design lets researchers do something powerful: connect a person’s performance on cognitive testing over many years with what was actually happening in the brain.

When you have repeated cognitive testing over a long window—often 10 to 20 years—you can see that cognitive change doesn’t always look like one smooth, steady slide. In these data, it often looks like two different “speeds,” with a bend between them.

Dementia is cognitive impairment that is severe enough to interfere with everyday independence, meaning it causes disability in daily activities. It is different from mild cognitive impairment (MCI), where changes are measurable but a person can still function independently.

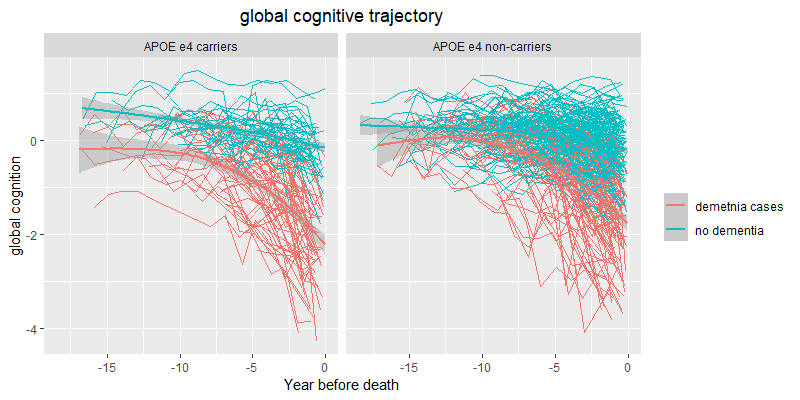

In the above spaghetti plots (credit to Xinhui Wang for the graphs), each thin line represents one person’s performance on cognitive testing tracked repeatedly over time, aligned by years before death. The most important thing to notice isn’t the year-to-year wiggle—scores naturally bounce with attention, sleep, mood, illness, and measurement noise—but the overall shape of the trajectory. Across both panels, dementia status dominates the picture: the no-dementia trajectories (teal) tend to cluster higher and often look relatively steady or only gently declining across the long stretch (about 10–20 years), whereas the dementia trajectories (red) more often show a stronger downward tilt and a visible acceleration closer to death. That acceleration is where the “terminal decline” window shows up visually: in the final ~3 years, many dementia trajectories bend into a steeper drop, while most no-dementia trajectories do not.

Preterminal decline is the long stretch—think the 10–20 years leading up to the final few years of life—when performance on cognitive testing may be stable for some people and gradually drifting downward for others. The key idea is that changes in this period are often slow enough to be subtle from one year to the next, even if they add up over time.

Terminal decline refers to a later window—roughly the last ~3 years of life in this dataset—when the average trajectory becomes noticeably steeper. Not everyone shows this in the same way, but when the pattern is present, it looks like a shift from a gentle slope to a sharper drop.

The bend (sometimes called a “change point”) is simply the transition between those two phases: the point where the preterminal slope accelerates into the terminal slope. It’s not a single dramatic day; it’s the place on the trajectory where the overall rate of change increases.

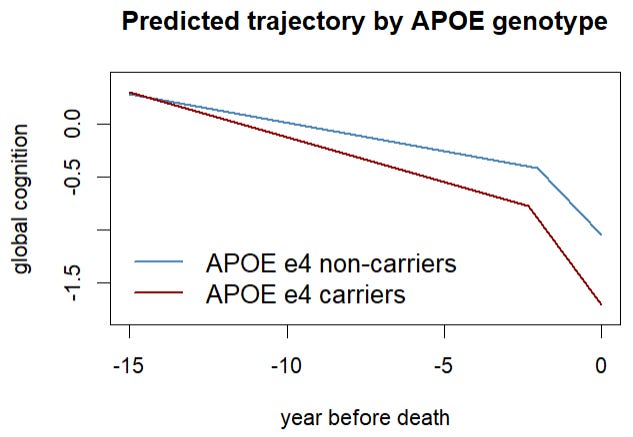

APOE ε4 doesn’t change cognition in just one way in this study. It shifts three parts of the “two-speed” pattern we’ve been talking about:

1) The long, slow stretch before the final years (preterminal decline).

Compared with non-carriers, people with APOE ε4 show a slightly faster slow decline during the long stretch leading up to the end. Think of it as a gentle downhill that’s a bit steeper.

2) The point where the line “bends” into a faster drop (the change point).

For non-carriers, the faster phase typically begins about 3.2 years before death. For APOE ε4 carriers, that bend happens earlier by about 9 months. In plain terms: the period of faster decline starts sooner.

3) The final fast-drop period (terminal decline).

Once the faster phase begins, APOE ε4 carriers also tend to decline more quickly than non-carriers in those last years. So the steep part of the slope is steeper.

One important nuance we learned from this ROS study: when researchers account for how much Alzheimer’s-related brain change (plaques and tangles) is present, most of these APOE ε4 differences get much smaller or disappear. That pattern strongly suggests the gene is linked to a worse trajectory mainly because it’s linked to more Alzheimer’s pathology, rather than acting independently on cognition.

ROS is powerful precisely because it isn’t a slice of the general population. In the ROS subset here (sample size = 411), participants lived to very advanced ages: the average age at death was 88.4 years (with a typical spread of about ±6 years). Importantly, longevity was similar in both genetic groups—APOE ε4 carriers died at about 88.0 on average, and non-carriers at 88.5. Education was also high in both groups (about 16–17 years on average). That combination—very old age plus high education—matters because it tends to be associated with what researchers sometimes call “reserve”: people can maintain day-to-day function longer even if brain changes are building underneath.

In ROS, you still see a clear difference in clinical outcomes by APOE status: 55.6% of ε4 carriers had Alzheimer’s dementia at death versus 32.0% of non-carriers. Put simply, in this ROS sample, about 56 out of 100 carriers ended life with Alzheimer’s dementia compared with about 32 out of 100 non-carriers. That’s a big gap—but it can still make genetic risk look smaller than it does in more diverse, population-based cohorts. That corresponds to roughly a 1.7-fold higher likelihood of dementia in ε4 carriers versus non-carriers.

Now contrast that with the UK Biobank, which is far closer to “big population data.” In that study, researchers tracked dementia risk over time and reported it as a hazard ratio, which you can think of as “how much more likely someone is to be diagnosed during follow-up.” Compared with people who had no ε4 alleles, those with one ε4 allele had about a 2.74× higher dementia risk. Those with two ε4 alleles had about an 8.66× higher risk. In everyday terms: one ε4 roughly tripled risk, and two ε4 copies increased risk by almost nine-fold in that population sample. UK Biobank also showed something that helps explain why ROS might look different: education changed how strongly APOE ε4 translated into dementia. Among people with one ε4, the risk estimate was lower in the high-education group (2.32×) than in the low-education group (3.61×). Among people with two ε4 copies, it was 6.63× in high education versus 12.15× in low education. That pattern fits the idea that education—and the life experiences that often come with it—can delay or reduce the chance that underlying brain changes become disabling dementia.

So what do we learn from ROS for prevention? Not that everyone needs to live like clergy, but that the “distance” between brain pathology and daily-life disability can be widened. ROS participants tend to have unusually consistent routines, stable social structure, and reliable access to care—conditions that likely support sleep, stress regulation, and management of vascular risks. Combined with high education, those factors may help people function well longer, even when Alzheimer’s pathology is present.

These features make ROS a kind of natural experiment in dementia resilience. The participants are not immune to Alzheimer’s disease—autopsies show plaques and tangles are common—but their lifestyles illustrate how much can be done to buffer risk, even in people with genetic susceptibility like APOE ε4. Lessons from ROS point toward prevention strategies that anyone can apply: maintain vascular health through regular exercise and blood pressure control, healthy dietary patterns, stay socially and mentally active, engage in lifelong learning, and cultivate consistent routines that reduce stress and support restorative sleep. The ROS experience reminds us that genes load the gun, but environment and habits often decide when—or whether—the trigger is pulled.

This is a terrific way to make APOE ε4 risk mechanistic and time-resolved rather than fatalistic. The “bend in the curve” concept (preterminal → terminal decline) is clinically clarifying: it suggests APOE ε4 isn’t just shifting whether decline happens, but when the acceleration window starts and how steep the final slope becomes and that much of the apparent genetic effect tracks with underlying AD pathology burden rather than an independent “cognition gene”.

What I also appreciated is the quiet but powerful prevention implication: reserve buys time. ROS reminds us that stable routines, strong social structure, and consistently managed vascular risk can widen the gap between pathology and disability, especially in high-education contexts, without pretending plaques/tangles don’t matter.

For readers, the practical takeaway I’d underline is: if you’re an ε4 carrier, the goal isn’t panic, but it’s earlier, steadier risk-friction reduction (BP, exercise, sleep/circadian regularity, metabolic stability, hearing, and cognitive/social engagement), ideally paired with objective monitoring when appropriate. This is exactly the kind of post that turns genetics into an actionable timeline rather than a sentence.