Semaglutide trial failures in Alzheimer's: missed opportunities to test the metabolic hypothesis of AD

For almost a decade, scientists have been intrigued by the possibility that Alzheimer’s disease might be, at least in part, a disorder of brain energy failure. The brain runs on glucose, and many early features of Alzheimer’s—reduced glucose uptake, impaired blood–brain barrier transport, neuroinflammation, and synaptic dysfunction—look like a prolonged energy crisis. That’s why GLP-1 receptor agonists such as semaglutide (Ozempic) drew such intense interest: in animal models and early human studies, GLP-1 drugs improved glucose transport into the brain, protected the blood–brain barrier, reduced inflammation, and enhanced neuronal metabolism. Mechanistically, they are one of the most biologically anti-aging drug classes to be tested in Alzheimer’s.

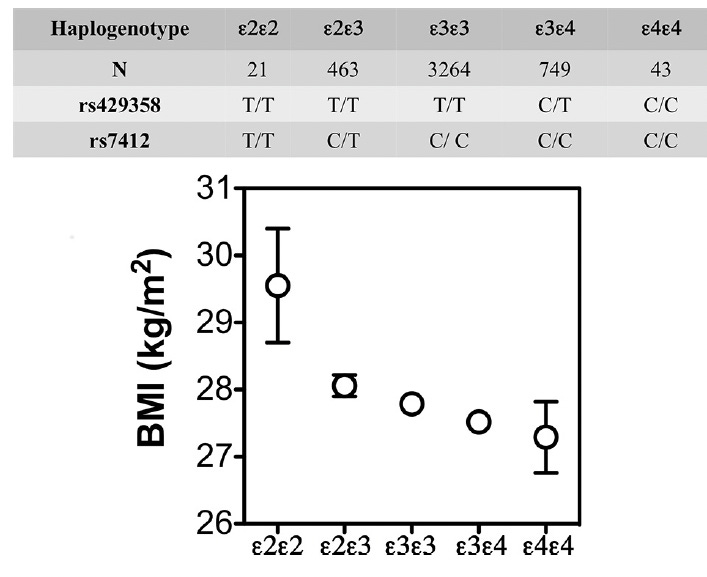

But metabolism becomes even more complex when we look at APOE4, the major genetic risk variant for Alzheimer’s. A growing body of work suggests that APOE4 brains rely more heavily on fat-derived fuels, have less metabolic flexibility, and respond differently to weight loss. In the Spanish Aragon Workers Health Study (n = 4,881) APOE isoforms were associated with body mass index (BMI) in rank order of APOE4 < APOE3 < APOE2. APOE2/E2 carriers (n = 21) had a greater BMI than the other isoforms. Adapted from Tejedor et al. (2014), Figure 1.

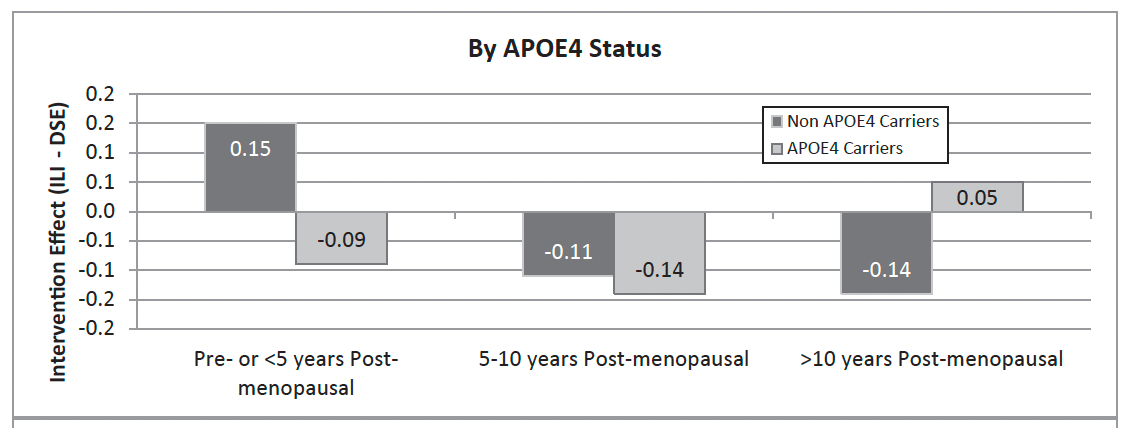

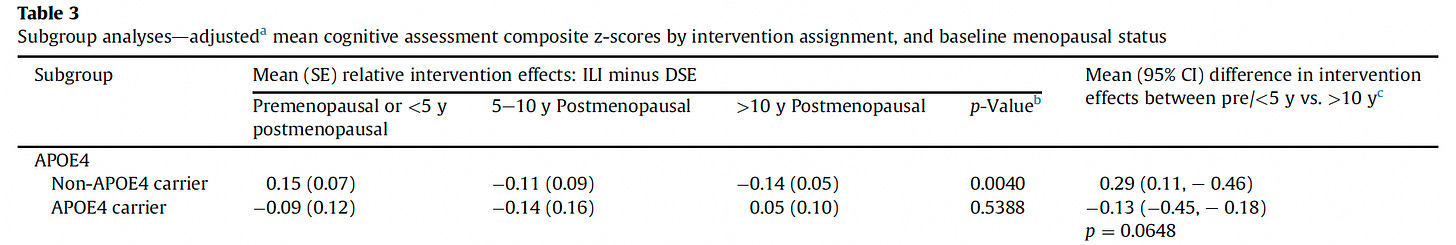

In APOE4 carriers—especially women—fat loss is consistently associated with faster cognitive decline, not improvement. Figure 2 below shows APOE4 women did not have any benefits from an intensive weight loss intervention on cognitive functions in a subanalysis of the Look AHEAD trial.

These observations help explain why weight behaves paradoxically across the lifespan: obesity in midlife raises Alzheimer’s risk, but in late life, low BMI and weight loss predict worse outcomes. Large cohort studies have shown this clearly: Luchsinger et al. found that in adults over 76, higher BMI became protective, while weight loss sharply increased the risk of both Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia.

This background matters because semaglutide is not just a metabolic modulator—it is also a powerful weight-loss drug. And that brings us to last week’s headline: the highly anticipated evoke and evoke+ Phase 3 trials—together enrolling 3,808 adults with early-stage Alzheimer’s—did not show that oral semaglutide slowed cognitive decline. While the drug improved Alzheimer’s-related biomarkers, it failed to move the primary clinical endpoint (CDR-SB). The trials were well designed and safely conducted, but the clinical benefit simply wasn’t there. The key scientific question now is: why did a drug with such strong mechanistic promise fall short?

The answer lies, at least partly, in who was enrolled. Participants in evoke and evoke+ were in their early 70s, already symptomatic (late MCI or mild dementia), and only modestly overweight: roughly 35% were overweight and just 15.5% were obese. In other words, these were not the metabolically high-risk, insulin-resistant populations where semaglutide exerts its most powerful systemic effects. Even more importantly, half the cohort had normal BMI, meaning semaglutide-induced weight loss may have been metabolically neutral at best—and cognitively harmful at worst—especially in older APOE4 carriers who may rely on fat reserves for brain energy compensation. The trial designers were aware of this risk and had flexible dosing and weight-monitoring protocols built in, but physiology is physiology: in a mixed population of older, partly normal-weight adults, weight loss can counteract the very metabolic support the drug is trying to provide.

Another limitation of evoke and evoke+ is that the enrolled population had very little vascular or metabolic comorbidity. Only about 1.4% of participants had documented small-vessel disease, and the prevalence of type 2 diabetes was just 13.6% across both trials—a low % for a cohort of adults in their early seventies. Moreover, the proportion of participants with vascular disease did not differ meaningfully between evoke and evoke+, suggesting that evoke+ did not achieve its goals. This matters because GLP-1 receptor agonists exert many of their strongest benefits in individuals with metabolic and vascular dysfunction—precisely the groups underrepresented here. The homogeneously low vascular-metabolic burden in these trials likely limited the opportunity for semaglutide’s vascular, endothelial, and anti-inflammatory effects to translate into measurable clinical benefit.

About 50% of the participants were APOE4 carriers, and the trials did not reveal genotype-specific differences in clinical outcomes. Still, given the heightened metabolic vulnerability of APOE4 carriers, this does not rule out the possibility that weight loss or catabolic stress could have offset some of the drug’s anti-inflammatory or metabolic benefits at an individual level. Based on the evoke and evoke+ results, we cannot argue that restricting enrollment to participants with BMI > 30 would have produced a different outcome. The trial data showed no variation in clinical response across BMI classes—normal-weight, overweight, and obese participants declined at essentially the same rate. It is plausible that age and disease stage, not BMI, limited the drug’s potential. These were adults in their early 70s with established, symptomatic Alzheimer’s, a point at which neurodegeneration, synaptic loss, and network failure may simply be too advanced for metabolic or anti-inflammatory interventions to translate into measurable clinical benefit. In this context, the absence of BMI-related differences suggests that the barrier was not body weight but the biology of late-stage, age-related neurodegeneration

Taken together, the data point to a possible interpretation: GLP-1 drugs may indeed improve some upstream biology in Alzheimer’s—metabolism, inflammation, vascular function—but in symptomatic 70-year-olds with substantial established neurodegeneration, limited metabolic dysfunction, and a high risk of harmful late-life weight loss, those upstream effects cannot translate into clinical slowing. The negative outcome of evoke and evoke+ does not disprove the metabolic hypothesis—but it misses when and in whom it is likely to matter. If GLP-1–based approaches are to succeed in Alzheimer’s, the next generation of trials may need to begin earlier (midlife or preclinical disease), focus on metabolically vulnerable groups (e.g., APOE4 carriers with obesity or insulin resistance), and avoid the unintended consequence of pushing metabolically healthy older adults with positive AD biomarkers (such as lean APOE4 carriers) into catabolic weight loss. The biology remains promising; this is not a time to stop investing in AD research!

Most smart Alz specialists agree the progression starts years before symptoms. Clinical trials test those that are 70 and symptomatic. I’m shocked. So unlike them.