Ketosis, weight loss, and the APOE ε4 brain

A 70-year-old man came for a second opinion on optimizing brain health.

He was worried for understandable reasons. Both of his parents developed dementia in their 80s. He had also undergone neuropsychological testing because he noticed cognitive changes. The testing showed objective mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Genetic testing showed one copy of APOE ε4.

After that evaluation, he started a ketogenic protocol that was presented to him as a way to prevent dementia. He followed it consistently for a full year.

Over that year, he lost ~25 pounds, and his BMI is now ~19.

His question was straightforward:

“Given my genetics and MCI, is staying in ketosis helping my brain—or am I pushing my body into a state that could backfire?”

This is the central tension: ketosis is often discussed as a brain-fuel strategy, but in real life it frequently comes bundled with weight loss, and weight loss can be biologically meaningful in older adults—especially those already symptomatic.

What ketosis is actually trying to accomplish

The ketogenic argument for brain health rests on a plausible idea: the brain can use ketones, and in Alzheimer’s disease brain glucose metabolism is impaired. Raising ketones might provide alternative substrate support.

The clinical question is not whether ketones can be used. It is whether raising ketones translates into meaningful, durable benefit in the population in front of us—older, symptomatic, and APOE ε4-positive—and whether the cost of maintaining ketosis (often weight loss and physiologic stress) is acceptable.

A second constraint matters in APOE ε4 and later-stage disease: there is evidence and mechanistic concern that ketone delivery and/or utilization in the brain may be impaired due to blood–brain barrier changes, transporter limitations, and mitochondrial dysfunction.

What human intervention studies suggest (focusing on larger samples)

Ketone-raising interventions in Alzheimer’s dementia: inconsistent efficacy, genotype signal

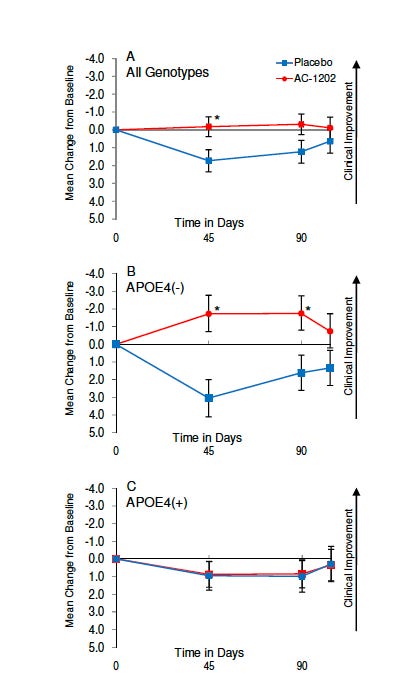

A randomized trial in 152 patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease tested a ketone-raising compound (AC-1202). The cognitive signal was reported primarily in APOE ε4–negative participants, with less evidence of benefit in ε4 carriers despite ketone elevation.

The figure above shows the mean change from baseline in ADAS-Cog score (which measures the severity of memory, language, and thinking problems in people with dementia, with a higher score indicating worse performance) over 90 days in participants randomized to AC-1202 (red) or placebo (blue). Assessments were performed at baseline (Day 0), Day 45, and Day 90. Panel A: all genotypes combined. Panel B: APOE ε4 non-carriers (APOE4−). Panel C: APOE ε4 carriers (APOE4+). Values represent mean ± error bars (as reported in the original study). The y-axis is oriented so that movement upward (more negative change) reflects clinical improvement (lower ADAS-Cog score), and downward reflects worsening. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between groups at the specified time point (typically p < 0.05).

A later multi-site trial using a related formulation (AC-1204) in 413 patients did not show overall cognitive benefit, with practical issues such as attrition and formulation/bioavailability discussed as limiting factors.

A careful, clinically honest read of this literature is: ketone-raising strategies can produce symptomatic signals in some settings, but the evidence is not consistent enough to treat ketosis as a broadly effective therapy for established dementia—and APOE genotype likely influences response.

Ketone-based intervention in MCI: a more plausible window, still not definitive

In MCI, ketone interventions may have a more plausible biologic window. A 6-month randomized trial in 82 participants with MCI using a ketogenic medium-chain triglyceride intervention reported cognitive benefits alongside evidence of increased ketone availability.

This matters for the case because the patient has MCI, not dementia. But it does not settle the question of long-term outcomes, and it does not answer whether sustained nutritional ketosis is required (or safe) in an older, lean APOE ε4 carrier.

The part that changes the risk–benefit analysis in this case: catabolic vulnerability

This case is not “ketosis in the abstract.” It is ketosis plus substantial weight loss in a 70-year-old with MCI.

In older adults, significant weight loss can reflect or contribute to:

lower physiologic reserve,

loss of lean mass and strength,

vulnerability to illness and stressors,

and (in some cases) a prodromal neurodegenerative trajectory.

Several large human datasets link late-life weight loss with higher dementia risk, and APOE ε4 can modify those relationships. For example, a long-term cohort of 1,462 women reported that APOE ε4 carriers with greater late-life weight loss had higher dementia risk.

Interventional data add nuance. In Look AHEAD (5,145 adults with type 2 diabetes and overweight/obesity), subgroup analyses suggest that cognitive effects of intensive lifestyle weight loss are not uniform across groups, and have been interpreted in the literature as consistent with the idea that weight loss may deprive some APOE ε4 brains of a relevant energy buffer.

None of this proves that weight loss causes dementia. But it supports a practical clinical posture:

In an older APOE ε4 carrier who is already symptomatic, substantial weight loss—especially to low BMI—should not be assumed to be beneficial for brain health.

Mechanisms: why APOE ε4 may increase sensitivity to catabolism

The mechanistic concern is not “thin is bad.” It is that APOE ε4 may be associated with differences in metabolic handling and adipose biology that reduce buffering capacity during stress. One mechanism includes the blunted PPARγ-related responses and adipose remodeling differences in APOE ε4 contexts.

Add one more layer: if later-stage disease limits brain ketone uptake/oxidation (BBB/transport/mitochondria),

then a patient may incur the systemic costs of restriction and weight loss while receiving less of the intended energetic benefit.

That is the catabolic vulnerability problem in one sentence.

Chronic ketosis can be physiologically stressful (especially in lean older adults)

Ketosis is not inherently harmful, but chronic nutritional ketosis is an active physiologic state with predictable stress points:

early diuresis (water/sodium shifts),

electrolyte needs,

and potential for muscle loss if protein and total energy intake are not adequate.

Early weight loss contributions include glycogen-linked water loss and ketone-associated natriuresis/diuresis, with clinical concerns such as dehydration and muscle loss risk with ketogenic dieting—along with mitigation strategies.

There is also evidence framed as a biphasic oxidative stress response (initial rise in oxidative stress markers with later adaptive signaling), consistent with a hormetic model.

Clinically, the relevance is straightforward: a physiologic stressor can be adaptive in one person (younger, metabolically impaired, high reserve) and costly in another (older, low BMI, already cognitively vulnerable).

Long-term feasibility and the LDL question in APOE ε4

Even if ketosis were metabolically helpful short term, long-term lifestyle ketosis raises two practical issues: adherence and cardiometabolic tradeoffs.

A 12-month randomized trial (n=118) comparing very-low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diets illustrates lipid tradeoffs over longer duration.

Across longer-duration comparisons, LDL-C can rise on very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic patterns in aggregate (with large meta-analytic datasets reporting LDL increases).

For APOE ε4 carriers, LDL is not a side detail. APOE ε4 is associated with higher LDL levels with diet-response considerations relevant to saturated fat intake and lipid handling.

So, even if a patient experiences some symptomatic benefit, a long-term pattern that worsens LDL may introduce competing vascular risk—highly relevant to brain aging.

Symptomatic benefit vs disease modification

This distinction should be explicit.

Most ketosis/ketone intervention studies are designed to test symptomatic outcomes (cognitive scales, function) over months.

A disease-modifying claim would require evidence that an intervention changes core pathobiology trajectories. At present, it is fair to say we do not have strong evidence that nutritional ketosis reduces phosphorylated tau or amyloid levels in humans or clearly modifies Alzheimer’s disease course over long horizons.

That does not rule out benefit. It simply sets the appropriate scientific boundary for “prevention” claims.

Who may benefit from ketosis—and who should be cautious?

This is where the discussion should land: matching the tool to the patient.

More plausible benefit profile

Ketosis (or other structured carbohydrate restriction) is most defensible when the primary target is a metabolic disorder:

obesity,

insulin resistance,

type 2 diabetes,

hypertriglyceridemia/metabolic syndrome.

In that setting, short-term metabolic improvements are consistently reported, while longer-term differences often attenuate and require careful attention to adherence and lipid response.

If a patient is younger, metabolically at risk, and not yet demented, the risk–benefit balance can be favorable—especially if weight loss is therapeutic rather than destabilizing.

Higher caution profile

For an older adult with established cognitive impairment and low BMI or ongoing weight loss, particularly with APOE ε4:

the downside of catabolism is higher,

the uncertainty around brain ketone utilization is greater,

and long-term lipid tradeoffs matter more.

Take-home messages

Ketosis can be helpful for some metabolically at-risk people—but it is not yet a proven disease-modifying tool for Alzheimer’s pathology.

In older adults with MCI, low BMI should be treated as a clinical risk signal, and the cost-benefit from ketosis should be discussed with a clinician.

APOE ε4 may shift the cost–benefit balance because of metabolic buffering differences and because ketone utilization in later-stage disease may be constrained.

Chronic ketosis can be physiologically stressful (fluid/electrolyte shifts, potential muscle loss), which matters more in lean older adults.

Long-term ketosis requires metabolic vigilance—especially monitoring muscle mass, metabolic stress signals and LDL cholesterol levels.

This is a really thoughtful post, because it tackles the question most people actually have (especially APOE4 carriers): “Can ketosis help me lose weight / improve cognition… without quietly worsening my lipid risk?” That’s the right framing, benefit is not one axis.

From a physician-scientist lens, a few points I appreciated (and would underline for readers):

1. APOE4 is a lipid-transport phenotype. Many APOE4 carriers are “hyper-responders” to higher saturated fat intake, with outsized rises in LDL-C and (more importantly) ApoB. So the same “keto success story” can look metabolically clean in one person and atherogenic in another, especially if the fat sources skew toward butter, coconut oil, and fatty processed meats.

2. Ketosis ≠ “high saturated fat.” The clinically safer version (if someone is drawn to low-carb) is often a Mediterranean-keto approach: emphasize unsaturated fats (EVOO, nuts, seeds, avocado), fish/omega-3 sources, plenty of non-starchy plants, and adequate protein, while monitoring ApoB, LDL-C, triglycerides, and LP(a) if available. That’s still low carb, but it doesn’t force the “sat fat experiment” on an APOE4 vascular system.

3. Weight loss can improve risk… while LDL/ApoB can still worsen. That paradox is exactly why lab follow-up matters. People can feel better, lower glucose, lower TG, and yet substantially raise ApoB, so a “good” response requires looking at both metabolic and atherosclerotic markers.

4. Cognition is tricky and individual. Some APOE4 carriers report clearer thinking on ketones (or with MCTs), but the long game has to prioritize cerebrovascular health too. In other words: a brain strategy that increases vascular risk is not a brain strategy.

If you wanted one practical “clinician-style” takeaway for readers: treat low-carb as an N-of-1 trial with guardrails; pick the fat sources wisely, track ApoB/LDL response at 6–12 weeks, and be willing to pivot (carb “re-introduction” via fiber-rich plants/legumes, or a more Mediterranean pattern) if the lipid side moves in the wrong direction.

Really valuable post for turning “keto for APOE4” from internet certainty into physiology + measurement + personalization.

Thank you again Dr. for the excellent post. (And the great comments). Very informative about a topic that is vague for APOE 4 carriers.