High dose omega-3s in end stage renal disease: what do we learn from the PISCES trial?

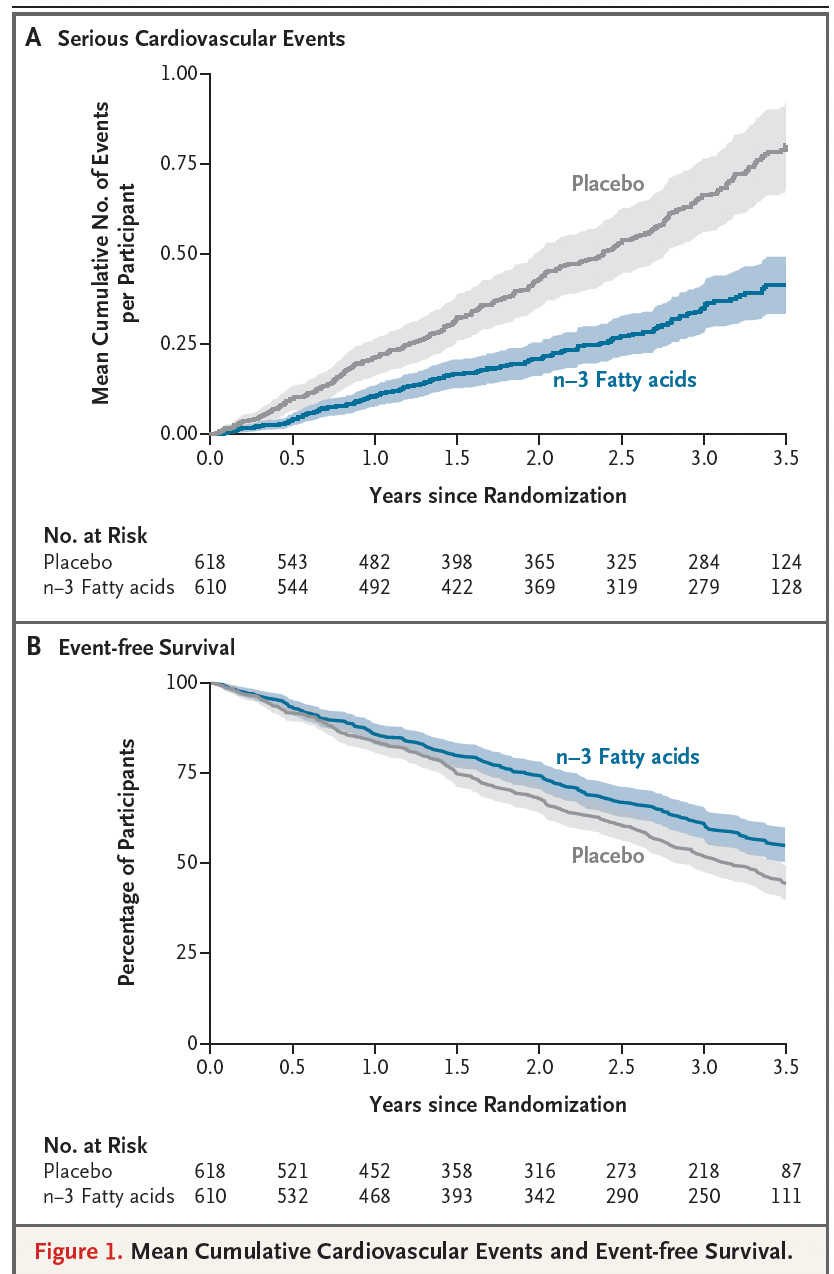

In the PISCES trial, 1,228 adults on long-term hemodialysis in Canada and Australia were randomized to receive either 4 grams per day of fish oil (1.6 g EPA + 0.8 g DHA) or a corn-oil placebo for 3.5 years. The primary endpoint—a composite of cardiac death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease requiring amputation—occurred far less often in the fish-oil group. The rate of serious cardiovascular events was 0.31 vs 0.61 per 1,000 patient-days for fish oil versus placebo, corresponding to a hazard ratio of 0.57. In absolute terms, 21% of fish-oil patients versus 34% of placebo patients had at least one major event over 3.5 years—an absolute risk reduction of ~13 percentage points, a relative risk reduction of ~38–43%, and a number needed to treat (NNT) of ~8. Meaning that for every eight people who took fish oil instead of placebo for 3.5 years, one major cardiovascular event was prevented, a level of benefit that is considered very strong for hard outcomes like heart attack, stroke, or cardiac death. The event curves diverged early and remained separated throughout follow-up. The figure below shows clear separation of the two groups after 1 year of treatment.

How does a high dose EPA work for cardiovascular event reduction? A biochemical substudy in this trial showed clear increases in EPA levels in plasma phospholipids among fish-oil recipients, confirming effective biological uptake. The exact mechanism by which high-dose EPA reduced cardiovascular events in PISCES is not fully defined, but several biologically plausible pathways have been identified. EPA is incorporated into cell membranes, where it competes with arachidonic acid and shifts the balance of lipid mediators toward less inflammatory and less pro-thrombotic eicosanoids. EPA also serves as a precursor to specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs)—including E-series resolvins, which actively turn off inflammation, promote tissue repair, and stabilize vascular and myocardial environments. In addition, EPA may reduce platelet activation, improve endothelial function, and stabilize cardiac ion channels, lowering susceptibility to arrhythmias.

How this trial stands out: The effect sizes seen in PISCES are large compared with many standard cardiovascular therapies. Typical statin therapy reduces major vascular events by 20–25% relative (hazard ratios ~0.75–0.80), often translating to 5–6 percentage points of absolute risk reduction over five years in high-risk patients and NNTs in the 18–40 range, depending on baseline risk. In PISCES, the ~13-point absolute reduction in 3.5 years is much larger because dialysis patients have extremely high event rates, frequent arrhythmias, chronic inflammation, and low baseline omega-3 levels. These conditions amplify the absolute benefit of any intervention that stabilizes membranes, reduces arrhythmia susceptibility, and modulates thrombosis. Earlier ESRD studies—including the FISH trial (which showed fewer cardiovascular complications as secondary outcomes), an EPA supplementation cohort demonstrating lower mortality, and observational work linking higher omega-3 levels to lower sudden cardiac death—had hinted at these benefits. PISCES provided the first large and definitive confirmation in this population.

What about DHA? EPA and DHA—the two major long-chain omega-3 fatty acids—play different biological roles. EPA tends to generate anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators, reduces platelet activation, improves endothelial function, and stabilizes cardiac ion channels, which can reduce arrhythmias. DHA, while crucial for brain and retinal membranes and also having anti-inflammatory properties, influences lipid profiles and membrane behavior differently and may not confer the same anti-thrombotic or anti-arrhythmic benefits. PISCES used an EPA-dominant formulation (40:20 EPA:DHA), and EPA levels rose clearly in treated patients. The physiology of dialysis—marked by oxidative stress, a pro-thrombotic state, endothelial dysfunction, and high arrhythmic risk—matches EPA’s mechanistic strengths more closely than DHA’s.

What about dementia? This is sharply different from Alzheimer’s disease DHA trials, which have largely been negative. A prominent trial of about 400 individuals with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s assigned patients to 2 g/day of DHA for 18 months and found no difference in cognitive decline despite adequate increases in blood DHA. Brain uptake was limited, especially in individuals with the APOE ε4 genotype. Alzheimer’s pathology develops over decades, producing amyloid and tau accumulation, synapse loss, and structural degeneration long before symptoms occur. Intervening at a symptomatic stage—using DHA alone, at moderate doses, for less than two years—is unlikely to reverse or meaningfully slow such long-established processes. The fast-acting cardiovascular pathways targeted in PISCES (arrhythmia, thrombosis, inflammation) are fundamentally different from the slow neurodegenerative processes in Alzheimer’s. Thus, it is not appropriate to infer that high-dose EPA or DHA would produce similar benefits for Alzheimer’s without long, early-stage trials specifically designed for neurodegeneration.

What about cardiovascular prevention? Large cardiovascular omega-3 trials outside ESRD also show how context determines efficacy. Many primary-prevention studies using ~1 g/day mixed EPA+DHA have shown minimal or no reduction in major cardiovascular events. Even high-dose EPA-only regimens in non-dialysis patients produce smaller absolute benefits (for example, NNTs around 20 over five years) than seen in PISCES, because baseline risks are much lower and background therapy (statins, ACE inhibitors, etc.) is more complete. PISCES succeeded because it applied a high-dose, EPA-dominant regimen in a group with very high cardiovascular risk, low omega-3 status, and mechanisms (arrhythmia, inflammation, thrombosis) that respond rapidly to EPA-based membrane and lipid-mediator changes. These factors do not generalize automatically to diseases with lower cardiovascular disease burden where timing, delivery, and pathology are very different.

Should we take high doses of EPA/DHA? High-dose omega-3 therapy has side effects and risks, which reinforces that it functions as a pharmacologic treatment, not a benign supplement. Common side effects include gastrointestinal discomfort, fishy aftertaste, and loose stools. Although omega-3s have mild anticoagulant effects, serious bleeding occurred slightly less often in the fish-oil group than in placebo in PISCES (4.8% vs 7.6%). In other populations, high-dose omega-3—particularly EPA-heavy formulations—has been associated with a small increase in atrial fibrillation, an arrhythmia that can raise stroke risk. DHA-rich supplements may also raise LDL cholesterol despite lowering triglycerides. These factors underscore that high-dose omega-3s should be used selectively, in conditions where evidence is strongest, and should not be assumed effective for Alzheimer’s disease or other chronic conditions without disease-specific, long-term randomized trials.

In conclusion: High-dose, EPA-dominant fish oil substantially reduced major cardiovascular events in hemodialysis patients, cutting risk from about one-third to one-fifth over 3.5 years, with no major safety concerns. This is one of the strongest cardioprotective signals ever seen in ESRD—a population where heart disease drives mortality and where many standard therapies underperform. While it doesn’t yet establish fish oil as universal treatment, it clearly indicates that EPA-heavy omega-3 supplementation is a promising, biologically plausible, and now well-supported strategy for reducing cardiovascular risk in dialysis patients, pending individualized clinical judgment.