From the Supplement Aisle to Evolving Science: Rethinking Omega-3s, Krill Oil, and Brain Health

I was at Costco recently, walking through the supplement aisle, when I noticed how much space is now devoted to krill oil and other omega-3 products. What stood out wasn’t any specific brand, but the scale of the display: multiple formulations, confident messaging, and an implicit promise that choosing the right version of DHA could meaningfully influence brain health. It felt like a snapshot of how ideas from nutritional neuroscience have migrated into everyday consumer culture—where complex biology is often distilled into simple decisions made at the shelf.

My perspective on this topic comes from more than a decade of work in our lab studying DHA, brain aging, and Alzheimer’s disease, with a particular focus on APOE4 carriers, who are at higher risk for dementia and appear to handle lipids differently across the lifespan. Over this time, the field has evolved from epidemiologic observations to mechanistic discoveries and large clinical trials. Some of the enthusiasm around omega-3s—including phospholipid forms highlighted in krill oil—is grounded in real biology. At the same time, parts of the narrative have moved faster than the clinical evidence. In this post, I want to take a measured look at what recent scientific studies support, especially for APOE4 carriers, and where important caveats remain.

Much of the phospholipid DHA story traces back to fundamental discoveries about how DHA enters the brain. The identification of the transporter MFSD2A showed that early in life, DHA that crosses the blood–brain barrier in the form of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC-DHA) is essential for brain development. These findings were later extended—speculatively—to aging and Alzheimer’s disease, particularly in APOE4 carriers, who may have altered blood–brain barrier integrity and lower omega-3 brain transport. A second assumption reinforced this extension: epidemiologic studies often suggest that fatty fish consumption is associated with better cognitive outcomes than omega-3 supplements. But fatty fish intake is also a marker of broader dietary patterns and lifestyle factors, and fish contain many bioactive components beyond DHA in phospholipid form. These observations do not isolate phospholipid DHA as the causal factor, nor do they show that supplementing a single molecular form reproduces the benefits of a healthy diet.

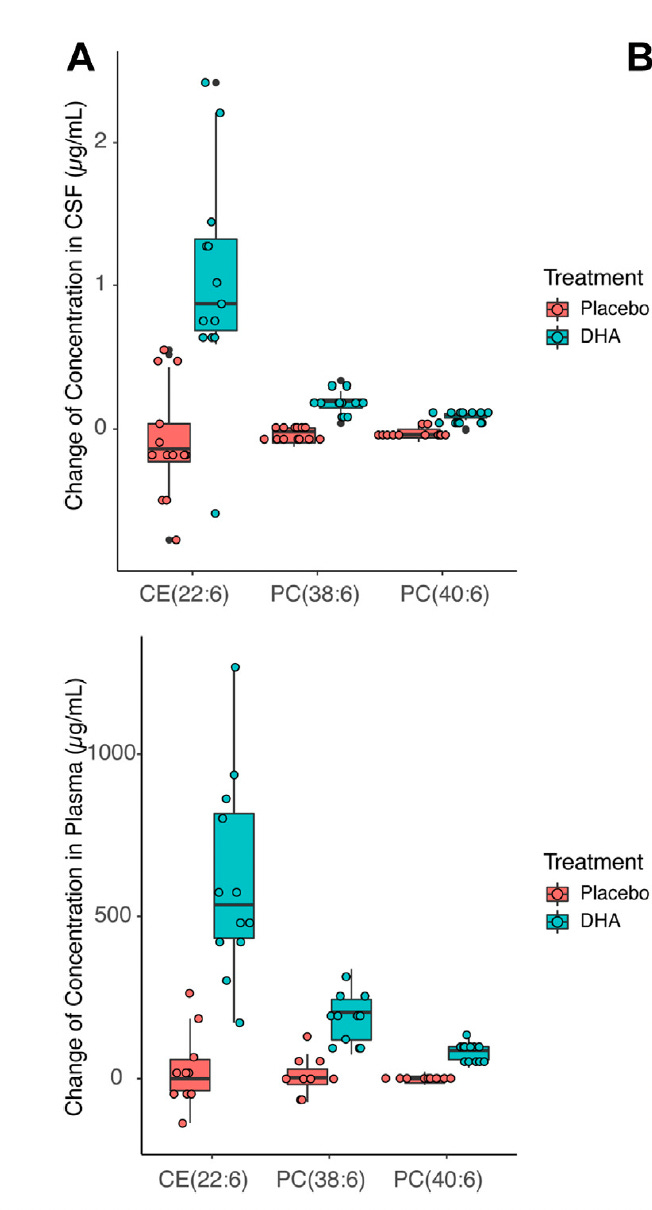

When we look closely at what happens to DHA after ingestion, the picture becomes more nuanced. Regardless of whether DHA is consumed as triglyceride, ethyl ester, or phospholipid, it is digested, absorbed, and extensively repackaged before entering circulation. DHA continuously cycles among triglyceride, phospholipid, and cholesteryl ester pools through lipoprotein metabolism and tissue exchange. We have shown that ingesting triglyceride DHA increases phospholipid DHA in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (Figure 1), consistent with equilibration across different lipid pools, arguing against a preference for one particular form of DHA. In the figure, CE stands for cholesterol ester, PC stands for phosphatidyl choline, which are lipid components of lipoprotein particles. The numbers refer to specific fatty acids; in this case containing DHA. By the way, krill oil is made of DHA and EPA bound to phosphatidyl choline.

Some initial studies suggested that phospholipid DHA formulations are more effective in reaching the brain. But a recent replication study by the Bazinet group in mice found that changing DHA formulation—including phospholipid and LPC forms—did not increase total brain DHA compared with other forms, despite clear systemic absorption. Together, these findings challenge the idea that consuming phospholipid DHA uniquely determines how much DHA ultimately reaches the brain.

The most important question, however, is whether these biological changes translate into clinical benefit, particularly for APOE4 carriers. Across randomized trials, omega-3 supplementation has produced mostly null cognitive results, including in older adults and Alzheimer’s disease. This does not mean omega-3s are irrelevant—especially for APOE4 carriers, who may be more sensitive to lipid imbalance and chronic inflammation. Evidence increasingly suggests that omega-3s may be most helpful when they are part of a broader, healthy dietary context.

APOE4 carriers consuming Western dietary patterns—high in saturated fat and low in fiber—are more likely to develop gut dysbiosis and systemic inflammation that may blunt the effects of supplementation. In contrast, fiber-rich, plant-forward diets that support a healthy gut microbiome and lower inflammatory tone may create the conditions under which omega-3s, including DHA, can exert meaningful biological effects. From this perspective, the expanding supplement aisle reflects genuine scientific interest—but the science itself points toward a more holistic conclusion: for APOE4 carriers, more omega-3s may be beneficial, but only when layered onto an overall healthy diet and lifestyle, not as a substitute for one. Converging kinetic, imaging, and epidemiologic evidence suggests that APOE4 carriers are uniquely vulnerable to dietary omega-3 deficiency and are most likely to benefit from sustained, long-term intake of DHA as part of an omega-3–rich dietary pattern—initiated earlier in life and supported by a healthy metabolic and less inflammatory milieu—rather than from short-term supplementation alone.

What this means for APOE4 carriers

Omega-3s still matter. APOE4 carriers tend to have altered lipid handling and may be more vulnerable to DHA insufficiency and inflammation. Adequate omega-3 intake remains biologically relevant.

Form is probably less important than context. Current evidence does not show that phospholipid DHA (e.g., krill oil) is clinically superior to other DHA forms for brain outcomes. After ingestion, DHA is extensively redistributed across lipid pools.

Dietary pattern sets the stage. Omega-3s are most plausible as part of an anti-inflammatory dietary pattern—rich in fiber, plant foods, and unsaturated fats—rather than layered onto a Western diet.

Gut health may be a key modifier. A diverse, resilient gut microbiome may be necessary for omega-3s to translate into downstream benefits, particularly in APOE4 carriers.

Supplements are not a shortcut. For APOE4 carriers, omega-3s should be viewed as a supportive component of a broader lifestyle strategy, not a stand-alone solution.

This is such a helpful “de-hype without dismissing” piece. I love how you walk readers from the shelf-level marketing claim (“phospholipid DHA/krill oil = better brain delivery”) to what the biology and kinetics actually suggest: once ingested, DHA is extensively digested and repackaged, cycling through multiple lipid pools, so the form on the label is unlikely to map cleanly onto brain delivery the way consumers are led to believe.

Your framing around MFSD2A/LPC-DHA is also the right kind of nuance: the transporter story is real and foundational in development, but extrapolating that to “therefore krill oil is superior for aging brains (especially APOE4)” is a leap that needs stronger human outcome evidence, particularly given the mixed/null cognitive RCT landscape and replication data challenging formulation superiority in brain DHA content.

Clinically, the most actionable takeaway is your “context first” message: omega-3s may be a meaningful supportive lever, especially for APOE4 carriers, but they’re most plausible as part of an anti-inflammatory dietary pattern (fiber-rich, plant-forward, metabolically healthier milieu), not as a shortcut layered onto a Western pattern. The supplement aisle is getting bigger; your post helps people get smarter.

Thank you for this evidence-based, thoughtful piece. As a physician in the longevity space, I hear a lot about omega-3 for health and longevity. The cardiac trials have mostly been null. You point at something similar for dementia and cognitive trials. For those who are not ApoE4 carriers, would you say omega-3 has even less benefit?