Could a Shingles Vaccine Protect Your Brain? The Evidence Is Getting Hard to Ignore

This story starts with a simple but powerful idea: the brain’s immune cells can burn out. In Alzheimer’s disease, the main cleanup crew—microglia—spend years immersed in low-grade inflammation, constantly responding to molecular danger signals instead of performing their usual maintenance work, such as clearing misfolded proteins or digesting amyloid-beta. Over time, they slip into an “exhausted-like” state: still inflammatory, still reactive, but increasingly ineffective at the very tasks that protect neurons. Strikingly, many of the strongest Alzheimer’s genetic risk signals point straight to this microglial stress axis. Genes like APOE4 regulate how vigorously microglia respond to threats, how long they remain activated, and how efficiently they phagocytose amyloid. In other words, our inherited biology can hard-wire microglia toward sustained, smoldering inflammation that gradually wears them down. Now add a second hit: a herpesvirus reactivation after decades of dormancy. Each episode is like tossing gasoline onto an already overworked fire brigade—pushing microglia deeper into immune exhaustion and further degrading their ability to clear toxic proteins. This emerging picture raises a striking question: if viral reactivations help drive microglial fatigue, could preventing those reactivations help preserve cognitive health?

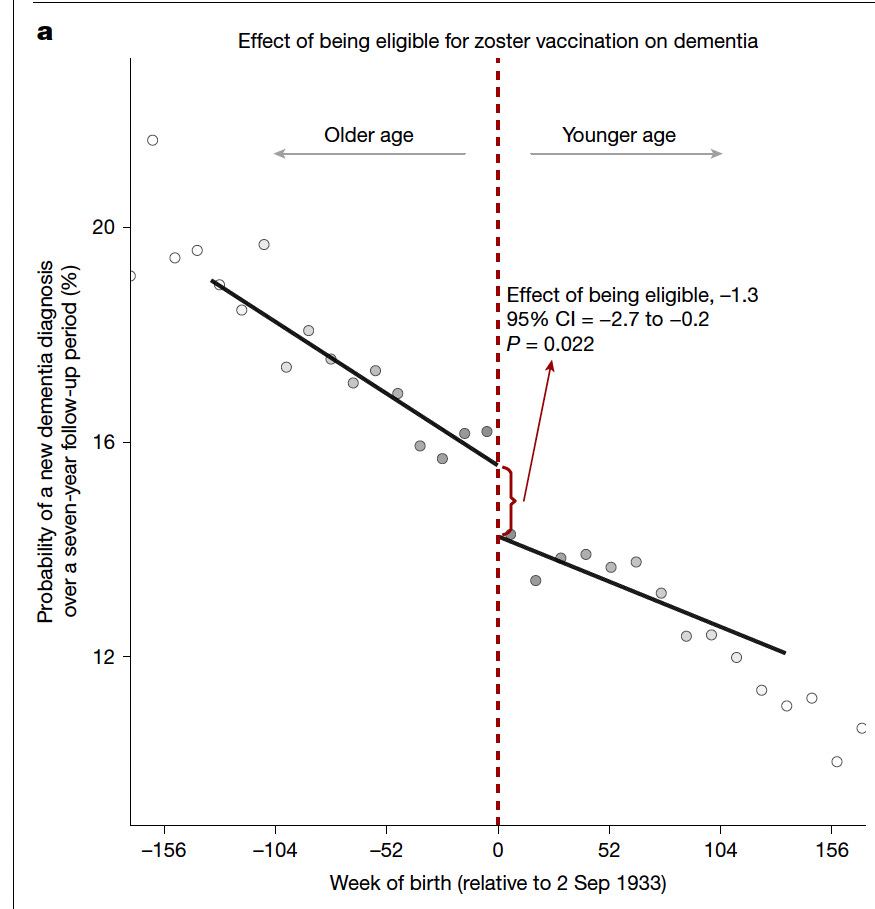

A Stanford team led by Pascal Geldsetzer and colleagues reported important advances on zoster vaccination and dementia incidence. Two recent natural experiments—accidental but scientifically powerful—suggest the answer may be yes. In Wales, a quirk in the shingles vaccine rollout created two nearly identical groups who differed only in vaccine eligibility. Individuals who received the vaccine were about 20 percent less likely to develop dementia over the next seven years.

Figure 1 shows a natural experiment created by Wales’ date-of-birth rule for shingles vaccine eligibility: people born just after September 2, 1933 were eligible, while those born just before were not, even though the groups differ in age by only days. By plotting dementia incidence against week of birth, the graph reveals a clear downward “jump” at the eligibility cutoff, indicating that those who could receive the vaccine developed significantly fewer dementia diagnoses over the seven-year follow-up. The estimated effect of eligibility is a 1.3 percentage-point reduction in dementia risk.

A few years later, Australia unknowingly created a near-clone of this design when it offered the vaccine only to those who turned 80 after a specific date. Again, two nearly matched cohorts—one eligible for vaccination, one not—and again, a significant drop in dementia diagnoses: 1.8 percentage points over 7.4 years.

A third study deepens the story by showing that shingles vaccination is associated not only with fewer dementia diagnoses but also with fewer cases of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), the earliest detectable stage of decline. Shingles vaccination was not only associated with fewer new dementia diagnoses, but also with slower progression and reduced mortality among people who already have dementia.

Across all three studies, a consistent narrative emerges: reducing herpesvirus reactivation may help stabilize the immune environment of the aging brain, especially in people genetically predisposed to microglial dysfunction.

Officially, these remain observational findings, even if they emerge from unusually rigorous quasi-experiments, and the scientific consensus is right to call for randomized trials before establishing any clinical recommendation for dementia prevention. Those trials will tell us whether the observed effects are causal, how large they truly are, and which groups benefit most. But science progresses on two tracks: careful experimentation and real-world decision-making. Millions of older adults—particularly those with APOE4 or strong family histories of Alzheimer’s—are already navigating choices about how to protect their cognitive futures. In that context, individuals and clinicians can make informed, evidence-aware decisions using what is known now about the shingles vaccine’s risks, benefits, and safety profile.

That framing leads naturally to a practical consideration: for someone at higher-than-average risk of dementia, what is the actual downside of receiving a vaccine that is already part of routine preventive care for older adults? The shingles vaccines used today—particularly Shingrix, the preferred non-live recombinant vaccine—have well-established safety records after millions of doses. Side effects such as soreness, fatigue, and fever are common but short-lived. Rare events like Guillain–Barré syndrome occur at only a few excess cases per million doses. For individuals carrying APOE4, whose lifetime risk of Alzheimer’s is several-fold higher, the balance of risks looks different: the probability of cognitive decline is already elevated, shingles itself is debilitating and inflammatory, and the emerging evidence suggests a plausible secondary benefit on dementia.

Current guidelines recommend Shingrix for all adults aged 50 and older, as well as for immunocompromised adults aged 19 and older, given as two doses 2–6 months apart. Unlike the older live vaccine used in the Wales and Australia studies, Shingrix is safe for immunocompromised individuals and is now the dominant global standard. Contraindications are limited—mainly severe allergic reactions to a previous dose or vaccine component, or deferring vaccination during a moderate or severe acute illness. In practical terms, Shingrix is accessible, routinely recommended, and has a safety profile that supports its broad use.

Rather than treating these findings as an endpoint, we should see them as the beginning of more focused research. The next step is to directly investigate how herpesvirus exposure and reactivation influence microglial metabolism, phagocytic capacity, and inflammatory tone in humans. Many questions remain. Does this apply only to the herpes Zoster? What about other viruses or infections? Can preventing reactivation slow or reverse microglial exhaustion markers? AD biomarkers? These epidemiologic findings do not close the case—they sharpen its central question. One new frontier in Alzheimer’s will require understanding how aging, genetics, and viral immunology converge on microglial function. This is why continuing to invest in the science of immunity in Alzheimer’s disease is an important topic to move the needle forward.