Blood Pressure and Brain Health: Why When Matters as Much as How Much

I recently saw an 85-year-old man in clinic because his memory has been declining.

Over the past year, he has had increasing difficulty remembering recent events. He no longer drives. His family notices that conversations repeat. These changes didn’t happen suddenly, but they are now affecting his daily life.

He has had high blood pressure for many years, and over the past 10 years, he started taking blood pressure medication consistently. At today’s visit, his blood pressure was 110/70, well within standard treatment guidelines.

His brain MRI, however, showed something important: moderate to severe white matter hyperintensities.

In this post, I will help explain why the relationship between blood pressure and brain health is more nuanced than a single number.

What are white matter hyperintensities?

White matter is the brain’s communication system—the wiring that allows different regions of the brain to talk to each other.

On certain MRI scans, areas of injury in this wiring appear bright. These are called white matter hyperintensities.

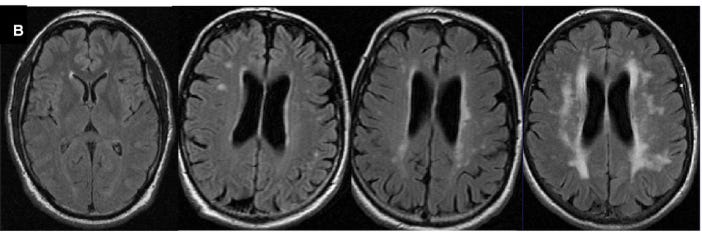

White matter hyperintensities are so named because they appear as bright areas in the brain’s white matter on water-sensitive MRI sequences (such as T2-weighted and FLAIR images, in the image below), reflecting increased tissue water from chronic small-vessel injury.

In plain language, white matter hyperintensities are signs of long-standing injury to the brain’s small blood vessels. High blood pressure is one of the most common contributors. Over many years, elevated or unstable blood pressure can stiffen and damage tiny vessels, making it harder for the brain to regulate blood flow smoothly.

White matter hyperintensities don’t appear overnight. They usually build up slowly, often beginning in midlife. When they become extensive, they can be associated with:

slower thinking and memory,

difficulty with balance and walking,

higher risk of stroke,

and higher risk of dementia.

They represent the brain’s vascular history written into its structure.

Genetics adds vulnerability: APOE ε4

This patient also carries one copy of APOE ε4, the strongest known genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

APOE ε4 does not mean someone is destined to develop dementia. Many carriers never do. What it does mean is that the brain is more vulnerable to injury, particularly injury related to blood vessels.

In people with APOE ε4:

the same blood pressure exposure can lead to more white matter damage,

cognitive effects may appear earlier,

and vascular risk factors play a larger role in shaping long-term brain health.

This makes prevention—especially earlier in life—particularly important.

What the science tells us about blood pressure control and dementia

One of the most consistent findings in brain health research is this:

High blood pressure in midlife is strongly linked to dementia risk later in life.

This relationship is especially pronounced in people who carry APOE ε4.

Large long-term studies show that:

elevated blood pressure in midlife predicts worse memory decades later,

persistent hypertension over many years increases dementia risk,

and much of the brain injury occurs silently, long before symptoms appear.

This is why blood pressure control in midlife is one of the most powerful tools we have for protecting long-term brain health, particularly for those with genetic vulnerability.

What did we learn from SPRINT MIND?

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) was a large, landmark study designed to answer a simple but important question: How low should blood pressure be treated to reduce cardiovascular risk? More than 9,000 adults with hypertension and elevated cardiovascular risk were randomly assigned to either standard blood pressure treatment (target systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg) or more intensive treatment (target <120 mm Hg).

SPRINT showed that targeting lower systolic blood pressure significantly reduced rates of heart attack, heart failure, and cardiovascular death. These cardiovascular benefits prompted a fundamental shift in how clinicians think about blood pressure targets—and raised the natural next question: could the same approach also protect the brain?

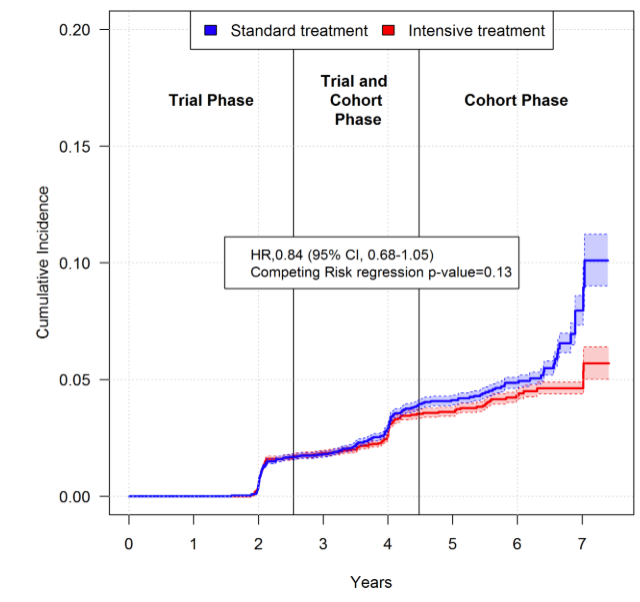

The SPRINT MIND trial tested whether aiming for lower blood pressure could protect the brain.

Adults over age 50 with hypertension were assigned to either:

standard blood pressure control, or

more intensive control with lower targets.

The results were important—but nuanced:

People in the intensive treatment group developed mild cognitive impairment less often.

Brain imaging showed slower progression of white matter injury.

The overall trend favored intensive treatment, although the study ended early and was not powered to definitively prove a reduction in dementia.

When researchers looked more closely, a clear pattern emerged:

The cognitive benefit was strongest in participants under age 75.

Benefits were less clear in the oldest participants.

Benefits were more apparent in people without advanced cardiovascular or kidney disease.

SPRINT MIND supports a central idea:

lower and stable blood pressure earlier in adulthood helps protect the brain.

It was a prevention trial—not a treatment for established brain disease.

Importantly, we still have gaps: we know that high blood pressure in midlife damages the brain, that APOE ε4 carriers are especially vulnerable, and that earlier, steadier blood pressure control appears protective—but we still lack a clinical trial designed to directly test blood pressure targeting in midlife APOE ε4 carriers. A pragmatic study is needed to determine when, how tightly, and for whom blood pressure control can most effectively protect long-term brain health using surrogate targets based on advanced imaging techniques of brain vessels and blood flow, before the onset of clinical dementia.

Where APOE ε4 fits

SPRINT MIND did not test genetic risk directly. But its findings align closely with what we know about APOE ε4.

APOE ε4 carriers:

accumulate vascular brain injury earlier,

show cognitive effects of blood pressure at lower thresholds,

and are more sensitive to long-term vascular stress.

Taken together, the evidence suggests that early, sustained, and stable blood pressure control may be especially protective for APOE ε4 carriers, before white matter injury becomes extensive.

Blood pressure is more than a number: stability matters

Blood pressure is not just about the average reading—it’s also about how much it fluctuates.

Dan Nation and his team have shown that large swings in blood pressure, known as blood pressure variability, place repeated stress on small blood vessels in the brain.

Higher variability has been associated with:

greater white matter injury,

faster cognitive decline,

and stronger effects in people with APOE ε4.

For brain health, steady control may matter as much as how low the number goes.

Why the message changes later in life

High blood pressure remains a major risk factor for stroke, heart disease, and vascular dementia at any age. That does not change.

What does change with advanced age is how the brain responds to blood pressure lowering.

In very old adults—especially those with:

cognitive symptoms,

significant white matter injury,

or long-standing vascular disease—

research suggests that lower blood pressure is not always more protective for the brain. In some cases, very low blood pressure in late life has been associated with worse cognitive outcomes.

There are several possible reasons:

the aging brain may have a reduced ability to regulate its own blood flow,

damaged small vessels may require higher pressure to maintain adequate perfusion,

and falling blood pressure can sometimes be a sign of evolving brain or systemic illness rather than protection.

This does not mean very high blood pressure should be ignored or left untreated in older adults. Rather, it means that aggressive blood pressure lowering is not automatically better for everyone, especially when cognitive impairment or extensive brain injury is already present.

In later life, the goal often shifts from “pushing numbers lower” to finding a blood pressure range that:

reduces stroke and cardiovascular risk,

avoids dizziness or falls,

minimizes large fluctuations,

and supports adequate blood flow to an already vulnerable brain.

These decisions should be individualized and discussed with a clinician—not made by patients on their own.

Bringing it back to the patient

In my 85-year-old patient, the MRI findings likely reflect decades of vascular stress, influenced by genetics.

At this stage, the question isn’t whether blood pressure matters—it does.

The question is what blood pressure range best balances brain perfusion, stability, and vascular protection for him now. That question is very different at 85 than it would have been at 55.

The broader lesson is that while blood pressure targets may need to be reconsidered and individualized later in life, hypertension should be identified and treated much earlier, when the brain is more resilient and long-term damage is still preventable.

Take-home messages

Blood pressure control is an essential component of dementia prevention.

The strongest opportunity for dementia prevention is in midlife, especially for APOE ε4 carriers.

Earlier, steadier blood pressure control appears to protect the brain later.

In older age, aggressive blood pressure control is not always more protective, and goals may need to be individualized.

Age-specific blood pressure targets should be discussed with a clinician, balancing stroke prevention, stability, and brain perfusion.

Pragmatic trials in mid-life with surrogate biomarkers ( e. g., advanced brain imaging of blood vessels) can help us better define these blood pressure targets in high-risk groups.

When it comes to brain health, timing, stability, and personalization matter—not just the number on the cuff.

Good presentation. BP is an important marker and target for AD types. Inflammation could be another outcome of poor BP management, impinging on brain health. Blood is the carrier of glucose, the energy source for brain, the major organ consuming energy. So, proper blood flow in the brain capillaries is very important. The lowering of bench mark to 120/80 from much higher figures in the past is not entirely unfounded, it is still not a fully convincing story. Some clue can be obtained by looking at past cohorts data, should be available, on cognitive impairment versus the higher BP bench marks, before serious medicinal interventions on BP upkeep became the norm. Some 50-60 years ago. But then, every thing is linked to everything else, body being a complex machine. Diabetes/ à la Insulin Resistance is an important marker, not only early on, but in advancing ages, on brain health. People call AD as Type 3 diabetes.