Blood-Based Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease: What They Reveal—and What Remains Uncertain

A 55-year-old woman sits across from me in clinic.

She has no memory complaints. She remains professionally active and fully independent. She found out using 23&me that she carries two copies of the APOE4 allele, a variant of the APOE gene associated with increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Her mother developed dementia in her mid sixties.

She has lived with the consequences of this disease.

When she reads that blood tests for Alzheimer’s disease are now available, she does not ask for a prescription or reassurance. She asks a more fundamental question:

“What do these new Alzheimer’s blood tests actually tell me?”

That question captures where the field stands today—between a genuine scientific advance and persistent uncertainty about prediction, interpretation, and ethics.

The central scientific advance: Alzheimer’s biology from blood

For decades, identifying amyloid plaques and tau pathology required amyloid PET imaging or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing—procedures that are invasive, expensive, and unevenly accessible. Over the past several years, plasma biomarkers, particularly phosphorylated tau species such as p-tau217, have demonstrated strong biological validity across multiple independent cohorts.

Across studies comparing plasma p-tau217 with amyloid PET or CSF reference standards, discrimination is consistently high. These findings have been replicated across memory-clinic populations and research cohorts using different analytical platforms.

This represents a meaningful shift: Alzheimer’s disease biology can now be assessed through blood with high fidelity.

FDA clearance of a specific assay (for example, Lumipulse) matters because it indicates that at least one platform meets standards for analytical performance and biological correlation. But the deeper change is conceptual: Alzheimer’s disease biology has become scalable.

Alzheimer’s biology is not Alzheimer’s dementia

Blood biomarkers bring renewed attention to a distinction that has always existed.

Alzheimer’s disease biology refers to amyloid plaques, tau pathology, and downstream neurodegenerative processes.

Alzheimer’s dementia is a clinical syndrome defined by cognitive decline and functional impairment that interfere with daily life.

The two are related, but not interchangeable.

Autopsy and imaging studies consistently show that many older adults harbor amyloid pathology without dementia. Conversely, many individuals who develop dementia do so with mixed pathology, including vascular injury, Lewy body pathology, neuroinflammation, and synaptic loss.

Blood biomarkers such as p-tau217 are strongest as biological indicators. They are inherently less precise as predictors of clinical trajectories, because dementia is not driven by amyloid alone.

What p-tau217 does exceptionally well

When the question is whether Alzheimer’s-type pathology is present, plasma p-tau217 performs extremely well. Studies comparing p-tau217 with PET and CSF biomarkers consistently report with Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) values above 0.90, often exceeding 0.95, for identifying amyloid positivity and tau pathology.

In this context, p-tau217 functions as a biological classifier.

This does not mean p-tau217 diagnoses dementia. It means it can often identify whether the molecular hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease are present.

Why predicting dementia is more difficult

The woman in front of me is not only asking whether amyloid or tau biology is detectable. She is asking what it means for her future:

Will she develop dementia?

When might symptoms appear?

How likely is progression?

These are substantially harder questions.

Dementia is a complex clinical outcome shaped by:

multiple pathologies beyond amyloid and tau

cognitive reserve and resilience

vascular and metabolic disease

inflammation and other neurologic processes

the time horizon being considered (five years versus fifteen)

Predicting dementia requires not only detecting pathology, but anticipating whether and when that pathology will become clinically expressed in a particular person.

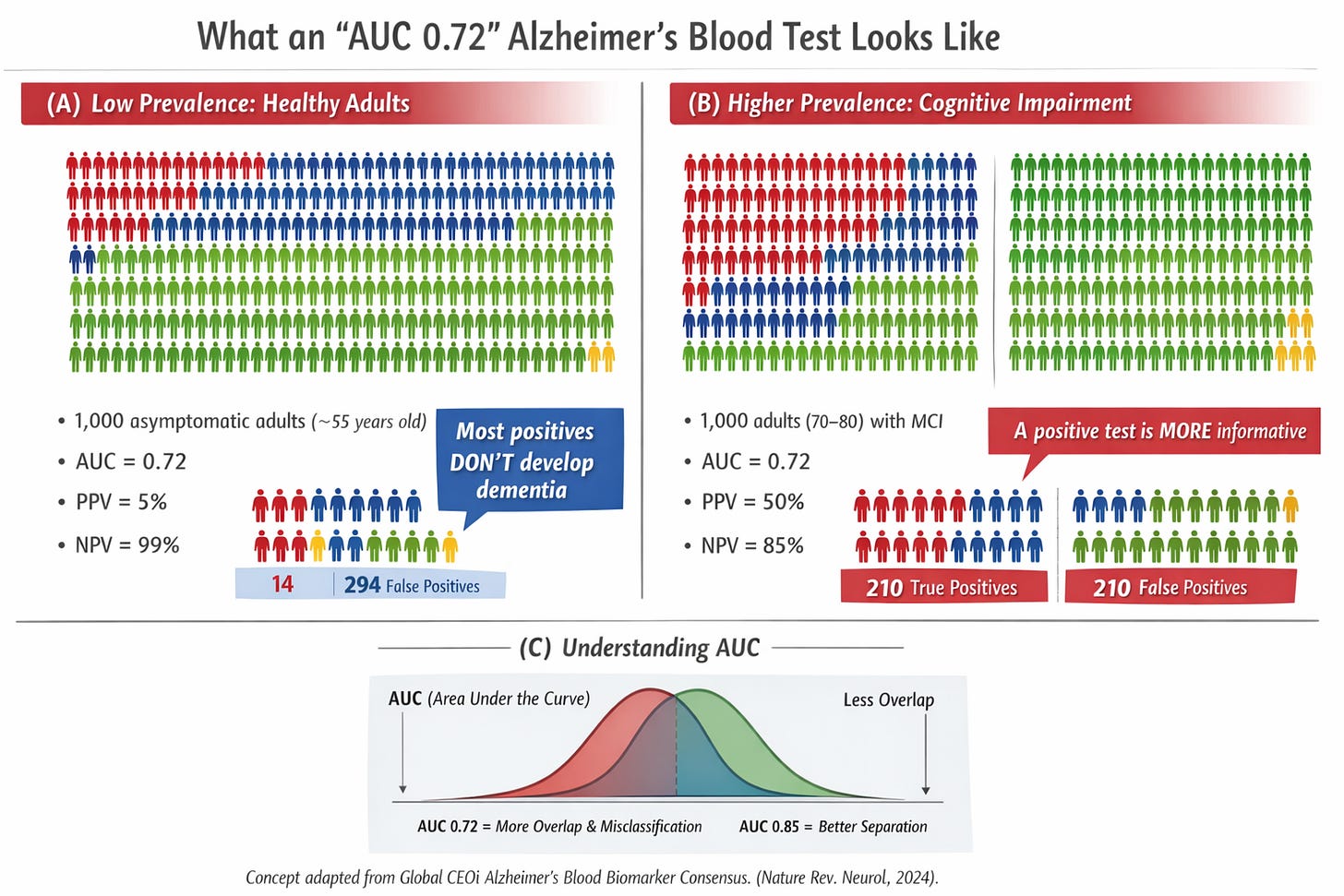

Understanding AUC, PPV, and NPV

Biomarker studies frequently report AUC, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). Each addresses a different aspect of performance.

AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve)

AUC is a measure of discrimination.

A practical interpretation is:

If you randomly select one person who will develop the outcome and one who will not, AUC is the probability that the test assigns a higher (“more abnormal”) value to the person who will develop the outcome.

AUC = 0.50 indicates no discrimination, coin flip

AUC ≈ 0.70–0.75 indicates modest discrimination with substantial overlap

AUC ≥ 0.90 indicates strong discrimination with limited overlap

AUC describes group-level separation across all possible thresholds. It does not indicate how many individuals will be misclassified at a specific cutoff.

PPV and NPV

PPV is the probability that a person with a positive test truly has—or will develop—the outcome.

NPV is the probability that a person with a negative test truly does not have—or will not develop—the outcome.

Unlike AUC, PPV and NPV depend strongly on baseline risk in the population being tested.

p-tau217 and dementia prediction: what an AUC between 0.7-0.8 implies

When plasma biomarkers are evaluated for future cognitive outcomes rather than current pathology, performance is more modest.

In population-based cohorts and prevention studies—often composed largely of cognitively unimpaired individuals—models incorporating p-tau217 (typically alongside age and baseline cognition) commonly yield AUC values in the low 0.70 range for predicting incident mild cognitive impairment or dementia over several years. One example is a large prospective study of 2,766 cognitively unimpaired women aged ≥ 65 years at baseline, where plasma p-tau217 measured with an ALZpath Simoa assay, was associated with future MCI and dementia over up to 25 years of follow-up. When combined with age, p-tau217 provided discriminative accuracy for incident MCI/dementia with an AUC of ~72 % in White women and ~70 % in Black women, showing similar performance across these groups (AUC ≈0.72).

This indicates a real signal, but also substantial overlap between those who will and will not progress over the observed timeframe.

Translating statistics into people: two illustrative scenarios

AUC alone does not uniquely determine misclassification; that depends on the chosen operating threshold. The following scenarios use a plausible operating point for illustration.

Scenario 1: the asymptomatic 55-year-old

Imagine 1,000 cognitively normal 55-year-olds, followed for ten years. Approximately 2% (20 people) develop dementia.

Using a test with 70% sensitivity and 70% specificity:

14 are correctly flagged and later develop dementia

6 are missed

294 are falsely labeled “higher risk”

686 are correctly labeled “lower risk”

Among those with a positive test, PPV is approximately 4–5%. Most positive results are false alarms.

Scenario 2: Adults aged 70–80 with objective cognitive impairment

Now consider 1,000 adults aged 70–80 with measurable cognitive impairment. Over several years, ~30% (300 people) progress to dementia.

Using the same test:

210 are correctly flagged

90 are missed

210 are falsely flagged

490 are correctly labeled lower risk

Here, PPV is approximately 50%.

The biomarker did not change. Context did.

False positives carry very different ethical weight in asymptomatic individuals than in people already experiencing objective cognitive decline.

Color legend

🟥 True positives

Individuals who test positive and go on to develop MCI or dementia during follow-up.🟦 False positives

Individuals who test positive but do not develop MCI or dementia during follow-up.🟩 True negatives

Individuals who test negative and do not develop MCI or dementia during follow-up.🟨 False negatives

Individuals who test negative but do go on to develop MCI or dementia during follow-up.

Familial hypercholesterolemia, APOE4, and limits of analogy

Cholesterol is often invoked as an analogy. The most appropriate comparison is familial hypercholesterolemia (FH).

FH is characterized by:

a well-defined biological abnormality, LDL-cholesterol > 190 mg/dL with a family history of premature heart disease

stable, standardized measurement

a strong and consistent link to clinical outcomes

interventions—such as statins—that clearly reduce morbidity and mortality

This alignment justifies measuring LDL cholesterol with an early diagnosis in people who feel well.

APOE4 homozygosity can feel similar emotionally. But important differences remain:

APOE4 increases risk but does not determine individual destiny

Amyloid positivity does not guarantee progression to dementia

Dementia is frequently multifactorial

Anti-amyloid therapies carry non-trivial risks, including brain swellings such as ARIA

ARIA risk is higher in APOE4 carriers

Preventive benefit in asymptomatic individuals has not been established

Unlike FH, Alzheimer’s pathology currently lacks a clearly effective, low-risk preventive intervention.

Biomarkers that became actionable: instructive contrasts

Some biomarkers transformed care because prediction and intervention aligned.

High-sensitivity troponin achieved very high discrimination for myocardial infarction, enabling rapid diagnostic pathways and immediate therapeutic decisions.

BRCA1/2 testing identifies individuals with markedly elevated lifetime cancer risk and offers actionable options such as enhanced surveillance or risk-reducing surgery, supported by outcome data.

In each case, strong discrimination was paired with interventions that changed outcomes and carried acceptable risk.

Looking ahead: when tests may become more actionable

Current limitations should not be viewed as permanent.

If future therapies demonstrate:

clear efficacy in delaying or preventing cognitive decline

favorable safety profiles suitable for long-term use

predictable benefit across biological risk strata

then the meaning of a positive Alzheimer’s blood biomarker could change substantially.

Just as cholesterol testing became actionable after the development of statins—therapies that were both effective and safe for people who felt well—a similar shift could occur in Alzheimer’s disease prevention and treatment.

In parallel, combining biomarkers such as p-tau217, with promising biomarkers such as neurofilament light, and GFAP with age and longitudinal cognitive change may improve predictive accuracy toward AUC values in the 0.8 range or higher in defined populations. Higher discrimination would reduce false positives, but actionability would still depend on the availability of safe, effective interventions.

The ethical tension remains

Blood biomarkers sharpen a fundamental dilemma:

What does it mean to diagnose a biological condition that may never become a clinical syndrome?

Potential benefits include improved understanding, better research, and earlier identification of risk. Potential harms include anxiety, stigma, and pressure toward interventions with uncertain benefit or real risk.

The challenge is not whether these biomarkers are scientifically valuable—they are. The challenge is how to use biological information responsibly when prognosis is uncertain.

Take-home messages

Blood-based biomarkers, particularly plasma p-tau217, represent a major advance in detecting Alzheimer’s disease biology.

These biomarkers perform exceptionally well for identifying amyloid and tau pathology.

Predicting future dementia is a harder problem; in general populations, AUC values around 0.7 imply substantial uncertainty.

AUC describes group-level discrimination; PPV and NPV depend strongly on baseline risk.

Context—age, cognition, and comorbid pathology—fundamentally alters interpretation.

Familial hypercholesterolemia is a useful comparison, but APOE4-associated amyloid does not yet have a comparable low-risk preventive intervention.

The actionability of these tests is likely to evolve alongside safer and more effective therapies.

Blood-based biomarkers provide an unprecedented window into Alzheimer’s disease biology. A clearer view of biology does not yet offer a clear forecast—but it accelerates the work needed to eventually change outcomes.

Thank you for this clear breakdown of AUC, PPV, and NPV as it relates to p-tau 217. Super helpful.

This is an excellent, timely overview! Blood-based biomarkers are finally making Alzheimer’s biology clinically scalable, not just academically interesting.

A few physician-scientist reflections that feel worth highlighting for our longevity-focused readers:

1. The real breakthrough is triage. Plasma p-tau species (especially p-tau217/181) and the Aβ42/40 ratio are increasingly useful for identifying who is likely to have underlying AD pathology and who may not, helping us reserve PET/CSF for the patients where it will actually change management. This is how we reduce “diagnostic wandering” while expanding access.

2. Context and pretest probability matter as much as the assay. In a low-risk, minimally symptomatic population, even a strong test can yield confusing positives; in an appropriate clinical context (progressive cognitive syndrome, strong family history, APOE4, etc.), these markers become far more actionable. Biomarkers should support the diagnosis, not replace the clinical story.

3. Think in panels, not single numbers. p-tau (AD-type tau pathology), Aβ42/40 (amyloid biology), and markers like NfL/GFAP (neuroaxonal injury/glial activation) answer different questions. Interpreting them together helps distinguish “AD pathology likely” from “brain injury is happening” from “something inflammatory/vascular/other may be driving symptoms.”

4. The ethics are huge. If we’re moving toward earlier detection, we owe patients clear counseling: what a positive result does (and doesn’t) mean, what downstream confirmatory testing is appropriate, and what evidence-based risk reduction steps are worth prioritizing today (vascular risk control, sleep/hearing, exercise, depression treatment, cognitive engagement).

Blood biomarkers won’t “solve” Alzheimer’s, but they can make the diagnostic pathway more precise, more equitable, and less invasive. Thank you for translating a fast-moving field into a practical framework without hype.